Tick-tock: Where will the U.S. find supply for growing LNG export demand?

By Jeff Bolyard, Principal, Energy Supply Advisory

In January 2016, the U.S. was a net importer of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) in the amount of 0.45 Bcf per day. Two months later, LNG exports exceeded LNG imports and averaged 0.38 Bcf per day of net exports of the super-chilled fuel.

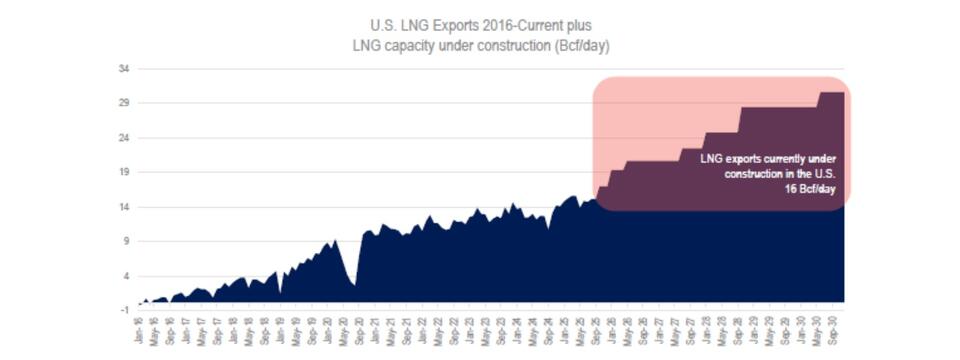

The chart below shows the significant growth over the past nine years, expanding in both the ability to export (capacity) and actual exported volumes, which peaked this year in April with an average of 15.5 billion cubic feet per day of net LNG and shown on the chart to reflect the exported volume from 2016-current.

That “tick-tock” sound the gas industry has been hearing in the background for about a year has been the slow but steady construction progress of a new wave of U.S. LNG export demand being built. Similar to the pre-digital sound of the alarm clock your grandparents used to fall asleep to every night, only to be violently awakened every morning, many in energy have been aware of the subtle, maybe even soothing sound of what this demand growth will mean. After all, exports peaked in April, even with the addition of a couple Bcf/day of capacity this summer. Those that yawned and rolled back over may be in for a rude awakening when the impact of 16 Bcf per day of LNG capacity currently under construction comes online over the next five years (highlighted right side of chart).

While there are several other LNG projects that have not reached FID or started construction, the 16 Bcf per day of growth highlighted on the chart is tangible, workers are onsite and active, and steel is being raised, with 5.5 Bcf per day of that capacity intending to come online in the next 6-18 months. The real question is: where will the physical natural gas supply come from?

The EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook published in July anticipates that a significant amount of the production needed to fill the growing demand by 2030 will come from the Appalachian region. Growth of Appalachian supply isn’t limited to availability of supply or even cost to access that supply. For Appalachian gas to meet LNG export demand, interstate infrastructure has to be built, which is not a short-term solution, nor is it without cost. For that to happen in the next five years, immediate action on bipartisan federal permit reform will be necessary. A wakeup call for bipartisan legislation where power transmission and facilities from renewable sources and pipelines that move natural gas to energy imbalanced regions of the U.S. is addressed before the rude ringing of the energy alarm clock will force the issue.

In the short term over the next 18 months, during which 5.5 Bcf per day of LNG capacity will be coming online, supplies will be forced to come from accessible shale plays closer to the Gulf, most likely dry gas from the Haynesville in west Louisiana/East Texas, associated natural gas from oil in the Permian, and the blended economics of both oil and natural gas in the Eagle Ford in south Texas. We are already seeing some growth in the form of added rigs in the Haynesville, which has increased 11 rigs since August 2024.

Outlets of natural gas from the Permian are in the works, which should help eliminate negative spot pricing that continues to plague natural gas producers. However, the addition of global supplies of crude oil into the market by OPEC+ over the past eight months has capped crude oil production prices and producer investment in the U.S., with drilling rigs down in the Permian by 39 rigs YOY in August. The silver lining is that there are 107 more drilled but uncompleted wells in the Permian in August 2025 than August 2024, so should gas prices turn positive for the region, gas economics will become a measurable slice of revenue rather than the current drag.

Unlike winter weather demand, which is always a wild card and may show up in force or may kick the can down the road until a year from now, 16 Bcf of incremental LNG export facilities are under construction in the U.S. and another 3 Bcf/day being developed in Canada and Mexico, all of which are being funded by companies and foreign governments that will want to get a return on their $5-$15 billion dollars per project to move LNG to markets outside the U.S. If you can’t afford the risk of that potential impact on domestic energy prices, protect it with an appropriate procurement strategy.