The data center wildcard and its regional impact on natural gas?

By Jeff Bolyard, Principal, Energy Supply Advisory

Last month, my writeup touched on the growth of LNG export demand, which has 16 Bcf/day of facilities under construction in the U.S., raising the question of where that gas will come from. Those facilities are all located along the Texas and Louisiana Gulf Coast in order to export to higher priced markets around the globe, leaving little guesswork as to where the ultimate demand will be focused regionally.

Less clear in the crystal ball, whether in terms of location, total demand, or impact on domestic natural gas supply and prices, is the demand for power for use in data centers. According to a report by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 4.4% of U.S. electricity consumption was consumed by data centers in 2023, with projections to nearly triple by 2028. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) estimates that data center demand will grow five-fold and add up to 120 GW of peak summer demand by 2030. Analysis shows clusters of data centers, both existing and planned, across the country, with certain states attracting the bulk of the growth.

What attracts data centers? In a BNEF survey, which asked data center developers which inputs into determining the site selection, the top three responses all had to do with energy, specifically:

- A secure, reliable connection to power

- Cost of energy

- Access to renewable/clean energy

However, due to a backlog of power interconnection queues and diminishing federal support for renewables, there has been a major shift in data center developer site location priorities. The new priority is no longer cost, even if the energy source is renewable. Rather, the new preference is speed to market. In other words, how quickly can you get my data center up and running reliably?

The combination of time crunch and reliability has shifted the discussion of fueling data center loads in the direction of natural gas, either with colocation of onsite power generation, or via partnerships with utilities and pipelines to arrange for infrastructure and physical supply. While there is definitely a desire for nuclear power, which will likely be a part of the overall energy solution, time is of the essence, which eliminates nuclear as a near-term solution with no less than nine separate nuclear partnerships announced between data centers and nuclear developers, including Google’s 25-year PPA for the repowered Duane Arnold nuclear plant in Iowa in 2029.

Coal is an option internationally, and likely the go-to fuel globally for AI growth, but in the U.S., natural gas will be the default fuel for data centers. Using data from BNEF, I modeled a handful of risk factors related to the additional demand for natural gas and ranked the top dozen states, initially by measuring the amount of MW demand for data centers that are either under construction or are financially committed to moving forward. Excluded from this analysis is the enormous number of data centers that have been announced but are less likely to materialize.

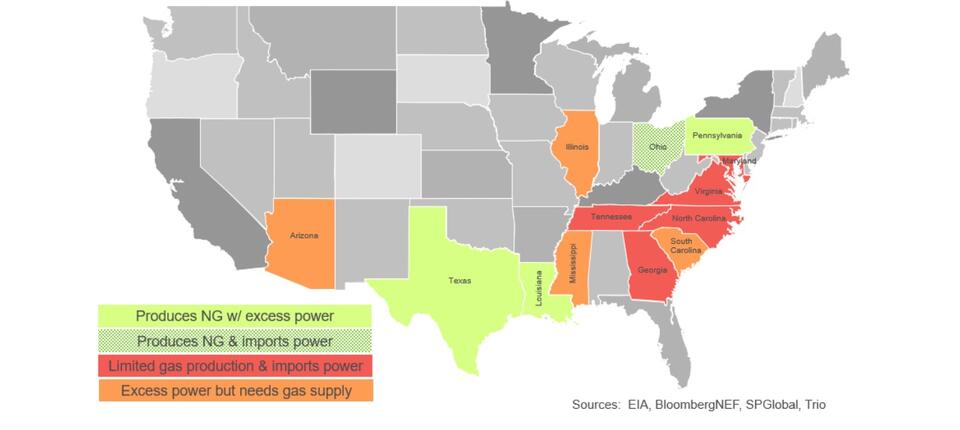

From this shortlist of states, I overlaid each with the most recent data from the EIA to show whether they can meet their existing power loads. States that do not currently produce enough power within their borders to meet existing demand will either need to build more in-state generation or import more power. Then I added a metric to each state that has announced plans to add natural gas-fired generation capacity of at least 1,000 MW. Finally, I layered on the likelihood of each of those states producing more natural gas within its borders, indicating the potential of increasing natural gas production without reliance on outside imports of either natural gas or power from bordering states.

The result highlights five states, colored in red, that have a) significant data center demand on the way b) import power today to meet existing demand and c) do not produce significant amounts of natural gas today. Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, and to an extent Tennessee, have a higher risk of natural gas reliability or pricing over the next several years. Tennessee is on the edge of this risk group, having similar fundamentals but also seeing significant amounts of natural gas passing through the state to higher priced markets, which could be dropped off at a premium rate.

The three states colored green—Texas, Louisiana and Pennsylvania—generate more power than they consume today and have access to additional supplies of shale natural gas production within their borders. As a result, they are more likely to meet the growing demand. Gulf Coast regions of TX and LA may experience increased price risk due to the growing LNG export demand, while indices further away from the coast could retain discounted basis longer until infrastructure increases market access.

Meanwhile, South Carolina, Illinois, Arizona and Mississippi, which export incremental power today, would need natural gas infrastructure to meet growing data center demand. These four could potentially utilize generation in-state to meet some level of growing AI demand, though they currently have a moderate risk of natural gas cost as well as reliability risk. IL is relatively diversified in its generation mix with significant nuclear assets; SC has a strong nuclear fleet; and MS and AZ both utilize natural gas as their primary in-state fuel to generate excess power today. However, due to their limited growth potential for in-state natural gas production, all four states will have to compete with their neighbors for the infrastructure to grow gas supply significantly.

Ohio is in a unique situation. The state produces significant volumes of natural gas and has access to Marcellus and Utica shales. In-state pricing is generally attractive: basis at Columbia Gas and Eastern Gas South Appalachian has historically traded at a significant discount to the Henry Hub benchmark. However, Ohio is a net importer of power today. While it has the natural resources to expand both production and subsequently generation, producers will only invest if prices are attractive. As AI demand grows, basis pricing should tighten. Similar tightening could occur in Pennsylvania and west Texas as intra-state infrastructure is built, and data center demand concentrates in less-served areas. Any mismatch in timing between new supply and new demand, whether real or perceived, could trigger short-term price volatility until the market rebalances.

Beyond the modeled risks, many forces will shape natural gas prices, including politics, regulations, and the ability to expand energy supply and build infrastructure for fossil, renewable, and nuclear generation. Bumps, curve balls and hiccups should be expected as the U.S. confronts physical constraints on data center growth. If AI demand ramps up in the wrong locations before supply is available, prices will swing. And in energy markets, volatility tends to show up quickly.

Want to dive deeper into how AI and data center growth are reshaping energy markets?

Check out our recent webinar featuring Trio’s energy and policy experts alongside Stan Blackwell, Director of Data Center Practice at Dominion Energy. The conversation explores how these shifts are playing out across power, gas, and regulation—and what industrial buyers should be watching now to stay ahead.